- Home

- Tom Angleberger

Fuzzy Page 4

Fuzzy Read online

Page 4

“Oh zar—er, smoke,” said Max. She stopped herself because her father still considered “zark” a bad word. But, really, thought Max, this is a totally zarked situation.

She had gotten so used to Fuzzy already that she hadn’t been thinking about what her mom’s reaction would be. And it would almost certainly be bad.

“OK,” she said, “but I wish you wouldn’t call him a ‘thing.’”

Her father shook his head. “Isn’t this the exact same conversation you had with your mother? Do you really want to get her all riled up again? And besides . . . it is a thing. A thing with a bad wig.”

Max groaned.

“He’s not—”

“Trust me, honey, I know what I am saying,” said her dad, who, in fact, did know a lot about robots because of his job writing high-tech instruction manuals. “I know it can seem real, but that’s because some company spent a lot of money to preprogram it to seem that way. Believe me. I just finished an instruction manual for a very friendly blender.”

Max rolled her eyes. If her father was having this much attitude about Fuzzy, she could hardly imagine what her mother was going to be like. Actually, she could imagine . . . and she knew she would rather avoid it altogether.

“I’ll get Fuzzy to call Jones and cut the visit short,” Max whispered to her father.

“I think that would be a good idea . . . and quickly, since Mom is due home from the library any minute now,” her father agreed. “Your mother has many virtues, honey. But love of technology isn’t one of them.”

Max went through the kitchen to the living room, where Fuzzy was still standing before the bookcase. “Uh, Fuzzy, I hate to rush you off, but maybe we’d better get you back to your people . . .”

“Of course, Max,” Fuzzy promptly agreed, and turned with her to the door. “It was interesting to meet you, Mr. Zelaster,” he said to Max’s father as they passed by him.

“It was interesting to meet you, too, Fuzzy.” He smiled at the robot, and Max could tell he was charmed by Fuzzy’s good manners. “You’re even better than the SwirlTec190,” her dad called as they continued through the front door.

Once they were outside, Max stopped and turned to Fuzzy. “You heard everything Dad and I were saying in there, didn’t you?”

It was fascinating to see a robot hesitate. Max felt as though she could almost hear gears and circuits whirring somewhere inside Fuzzy.

“Yes,” he finally admitted.

“Fuzzy! You’re not supposed to listen to conversations like that!”

“I cannot tone down my hearing. And unless I turn off voice recognition ahead of time, I cannot help but understand what is said. And I cannot know what type of conversation it is unless I have voice recognition on.”

Fuzzy stopped talking, but Max didn’t speak because she could tell he was thinking of what to say next. It must be pretty complicated if it’s taking him more than a millisecond to figure out, she thought.

“Max, I apologize if I have upset you.”

“No, I didn’t want you to apologize. I am just sorry that you heard all of that. I hope it didn’t—” Now it was her turn to hesitate. She was about to say “I hope it didn’t hurt your feelings,” but she realized that that was ridiculous. Or was it?

“I hope it didn’t interfere with your . . . uh . . . integration.”

“No. This has been very useful,” said Fuzzy.

“Well . . . good, I guess,” said Max. “I’m sorry we’re not being very polite, but, you see, my mom would blow a gasket if—”

“Max!”

It was her mom . . . and it sounded like she had blown a gasket already.

4.2

THE FRONT LAWN

Her mom was yelling from inside a silent solar car, which had just eased to a stop in front of their house.

“Will you unlock the door, you stupid thing!” she yelled at the car. One of her least favorite things about these automated PubliCars was the weird pause between their stopping and the unlocking of the doors.

When she finally got out, she slammed the door shut and stomped across the yard as the car eased back onto the traffic grid.

“Zarking PubliCars . . . I remember when we had real cars . . . ,” she muttered.

When she finally got over to Max and Fuzzy, she completely ignored Fuzzy and started right in on Max.

“Young lady, what’s your excuse for all these discipline tags you racked up today? They’ve piled up to the point where I even got a phone call at work this afternoon. Not just the normal text messages but an actual call from somebody at the Federal School Board!”

“What on earth is going on?” asked her dad from the front doorway.

“Haven’t you heard about all of her discipline tags today?”

“No, I wasn’t checking my phone. Maxine, why didn’t you tell me?”

Oh zark, thought Max, this is getting out of hand. Her parents were acting like it was the end of the world, and she couldn’t even remember what she’d done wrong.

“I—I—I didn’t know,” she stammered. “I mean, I knew I got one for being late to class, but that was a mistake. Dorgas was supposed to—”

“Late to class? Oh, no! That was just for starters. The lady had a whole list: ignoring rules, breaking rules, classroom disruption, bad attitude, and something called ‘stubborn willfulness.’”

“Stubborn willfulness?” Max yelped. “What the heck is that? Mom . . .”

“Carmen,” said her father, “can we finish this discussion inside . . . where the neighbors won’t hear the whole thing?”

“Good idea,” said her mom, moving toward the door. “Because . . .”

Her voice trailed off as she noticed Fuzzy for the first time.

“What in thunderation is this?” she demanded.

“Inside, please, inside,” said Max’s father.

“Well?” said her mother once they were all in the house.

“Hello, Ms. Zelaster,” Fuzzy said just as calmly as he’d have said it if he wasn’t being yelled at. “My name is Fuzzy. I am one of the students at your daughter’s school.”

“A robot? You have got to be kidding me! What on earth is it doing here?”

Max’s father tried to calm things down. “They thought that it might help him to go home with a student, and Max was—”

“Him?”

“Uh . . . Max, I thought you were calling them to pick him up?”

“Wait a minute,” said her mom. “Before ‘he’ goes, maybe ‘he’ can answer my question. Why does a robot need to go to school?”

“I am—” began Fuzzy, but Max’s mom was just getting started.

“I mean, what is the point? You can’t make a machine intelligent. It only knows what it’s programmed to know. Garbage in, garbage out. A chess-playing computer might make moves according to the way a board is set up, based on hundreds of thousands of other games programmed into its innards, but coming up with something original? Hardly! When it wins, it’s by imitating some game it’s dredged up from its computer banks.”

“Ms. Zelaster, you are absolutely right,” Fuzzy told her.

“What?”

“That is the problem with robots, computers, automated cars, all of them. They are helpless in every area except the one they’ve been programmed for.”

“Just what I— Huh?” Ms. Zelaster gave Fuzzy her full attention for the first time. “What did you say?”

“Robots are puppets,” said Fuzzy. “They can perform ‘tasks’ but not jobs. Can you imagine a robot doing a job with any originality, as any human could do?”

“Exactly!” said Max’s mom.

Max and her dad just stared. Was her mom actually agreeing with a robot?

“And that’s the whole problem,” continued her mom. “Nowadays everybody wants to let the computers do everything for them. Not only do the robots get it wrong half the time, but people are losing that individualism we used to have!”

Maybe that’s what “stubb

orn willfulness” is, Max thought. But wisely, she kept quiet.

“Ms. Zelaster, you are absolutely right,” Fuzzy said again. “Why, most people today do not even know what a book is. They believe that reading originated on the electronic tablets everyone has in some form. They cannot appreciate the binding and the artwork and the craft that goes into making an actual book, a work that you can hold in your hand, manipulate, feeling the texture of the page, appreciating the effort that went into its manufacture.”

Max’s mom was now just staring with her mouth wide open.

“Even the original science fiction writers realized this,” Fuzzy went on. “Ray Bradbury’s robots secretly took the place of human beings, making them like marionettes. Jack Williamson showed how robots would go overboard protecting us from ourselves—so much so that humans would not be allowed to do what they liked. Arthur Clarke’s HAL sabotaged the space mission he was on. Even Isaac Asimov, who insisted that his fictional robots were programmed to harm no one, would not have had any stories if he hadn’t found flaws in the programming each time.”

Max’s mom’s mouth opened even farther. And Max realized hers was hanging open, too. Somehow, Fuzzy had tapped into some of the same things her mother complained about all the time—or at least until Dad called it enough and insisted on changing the subject.

“You . . . you know about those old sci-fi stories?” her mom asked.

“Oh, yes. In many ways, we are living in the science-fiction world those old stories projected. But we have neglected the warnings those stories often gave us.”

“But how do you know about Bradbury and those other writers?”

“A survey of literature was part of my programming,” Fuzzy said. “I assume it was part of the effort to humanize me. And all those stories in the past have left their mark on our present.”

“Well,” said Max’s mom, “did you know that the very word ‘robot’ was coined in a play, and later a book, by a writer named Karel Capek way back in 1920? And his robots revolted against the people in charge . . .”

Max and her father exchanged a look and then slipped into the automated kitchen to let Fuzzy and her mom talk sci-fi.

“OK,” said Dad. “I take it back. That is no blender! That is amazing! How on earth is he doing that?”

“I think I’ve got it figured out,” whispered Max. “Remember when he was looking at the bookshelf? I figured it was just because he had never seen actual books before. But he must have been downloading the e-book versions from the net and analyzing them.”

“But why would he do that? Don’t tell me he was programmed to go around downloading random books?”

“He wasn’t,” said Max, noticing that her dad was now calling Fuzzy a “he,” not an “it.” “He programs himself, and I think he just does whatever he wants and he was curious.”

“Hmm,” said her dad. “Don’t be so sure, Max. Every robot, every computer, has been programmed. Even if he is writing new code for himself, somewhere deep inside is a core program written by some person . . . for some purpose.”

4.3

THE DINING ROOM TABLE

There was no longer any question about whether Fuzzy would stay for supper. Max’s mother was delighted to have found another sci-fi fan and was eager to talk even more.

When she went to program the food dispenser, Max finally got a chance to talk to Fuzzy.

“That was amazing,” she said. “You downloaded the books on our shelves, right?”

“Yes,” said Fuzzy.

“And you had time to read them?”

“Yes, I have a subroutine for analyzing literature. However, I may not understand a book as well or in the same way as a human does.”

“Well, you seemed to have figured out those pretty quickly,” said Max. “But how did you know they were Mom’s and not my dad’s?”

“Some of what your mother was saying was reflected in those books. And I thought that your mother would be the one to enjoy having old-fashioned paper copies, given that your father has a background in technology and would be more likely to do his pleasure reading with an electronic device.”

Max shook her head in amazement. “You’re learning, Fuzzy! Fast!”

But a moment later, Fuzzy showed how clueless he could still be.

When they went to sit down around the table, they were one chair short.

“Oh, let me go get a chair from the guest room,” said Mrs. Zelaster.

“No, thank you,” said Fuzzy. “I do not need a chair.”

And he lowered himself to the correct height.

Max looked under the table and saw that his legs were in what looked like a very uncomfortable squat, at least for a human. In fact, she realized, one of his knees was bent backward. It was disgusting, and when she looked up she saw that her parents had seen it, too.

It was an awkward reminder to all of them that this wasn’t a human after all.

“I’ll get the chair,” said Max, jumping up.

Unfortunately, by the time she returned, the conversation had completely stalled, and her mother had remembered where it all started.

“All right, Max,” said her mother, no longer shouting, but calm and logical, which Max knew was often worse. “Your ‘friend’ here may be a fun distraction for you, but we can’t have all these discipline and test problems piling up on you. You have got to start really concentrating on important things.”

“Well, Mom, I—”

“Uh-uh.” Her mom held up a hand. “I’m not finished. Not even close. Acting like a companion to a robot may be a big deal among your friends at Vanguard, but you can’t play the hotshot at school when you’re failing your tests.”

“I’m not acting like a hotshot!”

“But you are failing the tests, Max,” said her dad. “You promised us you were going to study and bring your scores up. Look, I just downloaded the report from your school, and your scores are actually worse this week!”

He held up his communications pad to show Max the report Barbara had sent. It was an animated line graph, and her mother got more and more upset as it played.

“Do you see that line?” her mother asked. That’s your test scores! And this one is discipline! And . . . oh, Max . . . this is the overall #CUG score. That’s the big one, right? Well, it looks like a stock market crash! Do you see that?”

Max stared at it. It did look pretty bad.

“Your mother asked you a question: Do. You. See. It?”

“Yes, I can see it!”

“Don’t give me that attitude!” said her mom. “We don’t need attitude—we’ve got plenty of attitude—what we need is for you to study!”

“I did study! Honest, I don’t know how I could have failed. I knew those answers!”

“Don’t sit there and say you knew the answers when you obviously didn’t. Do you think this doesn’t matter? Do you know what the person from the school board told me? They told me that you may have to take remedial classes . . . at the county EC school!”

Max froze. EC school?

EC stood for ExtraChallenge. Supposedly it was a school for students who needed a little extra help UpGrading, but everyone said the EC schools were full of bad kids and really bad teachers. Max wasn’t even sure where the actual school was.

“From what I hear,” said her dad, “once you get sent to EC school, you’ll never catch up.”

That was what Max had heard, too.

“Oh, Max,” said her mother, “you’re going to end up just like Tabbie Filmore.”

Tabbie had been a friend of Max and Krysti who started the year at Vanguard but didn’t last long. She was weird and hilarious but also smart. Or at least she had seemed smart. But then she started flunking the UpGrade tests. One day she told Max and Krysti some school board official had actually come to her house to tell her parents she would have to be transferred to the ExtraChallenge school if she didn’t do better. She didn’t, and one day she wasn’t at school anymore.

(Al

l this time, Fuzzy just sat there. But he was busy. He downloaded Max’s records. And then Tabbie’s. He looked at the EC school’s statistics. This wasn’t public information, of course, but the school system’s password was easily bypassed.)

“You should not go to the ExtraChallenge school, Max,” Fuzzy said.

“Ugh! Not you, too!” groaned Max. “Trust me, I don’t want to!”

“Well,” said her mother, “then Fuzzy better go home, and you better go study.”

“I am contacting Jones,” said Fuzzy. “He will be here in approximately forty-five seconds, based on the van’s present location.”

4.4

MAX’S HOUSE

Fuzzy got up and very politely thanked the Zelasters for dinner—even though he hadn’t eaten anything—and for the lovely evening, even though it hadn’t been lovely.

When they had been preparing Fuzzy for the Robot Integration Program, Nina had sent him links to several websites about manners and etiquette and he had created a long list of PoliteBehavior() code.

So when Fuzzy thanked the Zelasters, he was just running the appropriate code. That’s what robots and computers do, after all. And when they can’t find the appropriate code, they either do nothing or generate an error message.

But not Fuzzy. When Fuzzy couldn’t find the right code, he started writing it himself. This was what he was built for. To make a plan to fix an error, not just report it. To keep going . . . like a human has to.

And all through that dinner, listening to Max and her parents, Fuzzy had tried to find the appropriate code for the trouble Max was in. But he couldn’t. The problem didn’t even make sense, he realized: The scores showed that Max was not smart, but his own analysis showed that she was smart.

Smart = not smart. It just didn’t work. Something was wrong. He needed to fix it. In fact, he wanted to fix it.

Robots aren’t supposed to want things. They are not supposed to like one person better than another person. They aren’t supposed to do things they are not programmed to do.

Fake Mustache

Fake Mustache Horton Halfpott; Or, the Fiendish Mystery of Smugwick Manor; Or, the Loosening of M’Lady Luggertuck’s Corset

Horton Halfpott; Or, the Fiendish Mystery of Smugwick Manor; Or, the Loosening of M’Lady Luggertuck’s Corset Inspector Flytrap

Inspector Flytrap Inspector Flytrap in the President's Mane Is Missing

Inspector Flytrap in the President's Mane Is Missing Darth Paper Strikes Back

Darth Paper Strikes Back Double-O Dodo

Double-O Dodo Didi Dodo, Future Spy: Recipe for Disaster

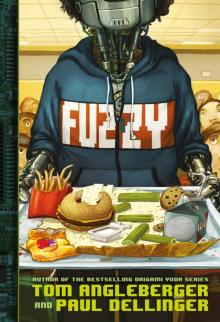

Didi Dodo, Future Spy: Recipe for Disaster Fuzzy

Fuzzy Star Wars

Star Wars Inspector Flytrap in the Goat Who Chewed Too Much

Inspector Flytrap in the Goat Who Chewed Too Much Beware the Power of the Dark Side!

Beware the Power of the Dark Side! Horton Halfpott

Horton Halfpott